Formidable Armida (Part Two)

In spite of its historical pretensions and its status as one of the great heroic epics, or perhaps alongside with them, Gerusalemme Liberata is ultimately a romance. And a romance is never far away from the fairy-tale. It is populated by the same kind of characters: brave young men and beautiful princesses, proud kings and wicked witches. Rinaldo and Tancred, Clorinda and Erminia, Godfrey and his dark equivalent Aladdin, and of course the great Armida are the sort of people one would encounter in the land of Faerie. But we really know we have arrived there when our heroes walk into enchanted places, by chance or by design.

In Canto Seven, Tancred finds himself in a place which screams ‘Faerie’ a mile away. He was persecuting Erminia, whom he had taken for an enemy warrior but lost her, and wandering far away, he ends up in

a nearby forest thicket, whereupon / so dense the windswept trees grow roundabout, / so black and fathomless the shadows yawn, / that soon he grows unable to make out / more recent footprints, and, perplexed, rides on.

It is night time and Tancred is lost in this forest, where ‘the faintest night-breeze rustles through / the twigs of elm or beech with feeble force’. The awe inspired by a forest at night-time is legendary: it is the deep archetypall fear of the wild, of the desert where no civilized person would go willingly, a cultural shock memory deeply impressed on European sensibilities ever since the Romans tried (and failed) to conquer Germania with its impenetrable forests. As medievalist Jacques LeGoff put it:

‘the face of Christian Europe was a great cloak of forests and moorlands perforated by relatively fertile cultivated clearings … a collection … of manors, castles, and towns arising out of the midst of stretches of land which were uncultivated and deserted … It was rather like a photographic negative of the Muslim east which was a world of oases in the midst of deserts.’ (1)

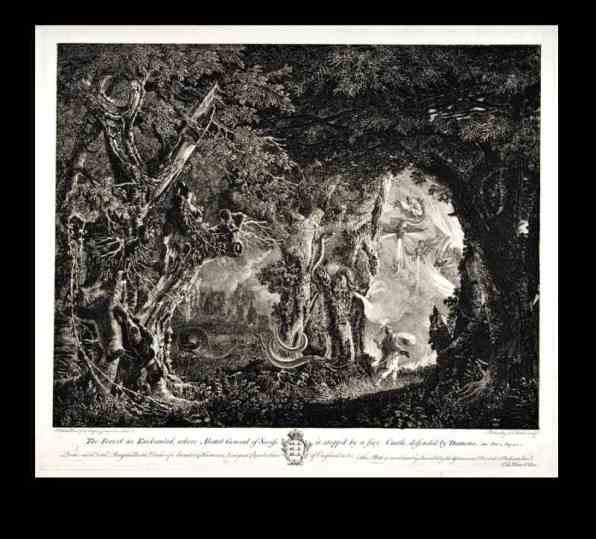

Tasso transposes the world of European Faerie onto the Holy Land, placing a dark forest there (and not the only one, as we shall see later). Tancred wanders in the forest all night, but eventually reaches a clearing. It is noteworthy that, although the forest is scariest, it is the clearing in its heart that holds the real danger – witness Circe’s palace in The Odyssey. There, ‘a distant hum’ leads him to the banks of a river. He is completely lost and all alone, when at last someone approaches:

[He] soon hears hoof-beats ever nearer, and / at last out of a narrow pass there flung / a man – a courier, by his look. His hand / held a little whip, and from his shoulders hung / a great horn, in the fashion of our land.

So far, so good: Tancred is reassured by the recognizable cultural signs – the horse, the whip, the horn of the courier. What is more, the man tells him he is sent by Tancred’s own uncle, Bohemond. ‘Tancred goes with him’, we are told, ‘thinking him sent by his famous uncle, and his false tale sound.’ Oops! A warning sign! And very soon Tancred himself is on the alert too:

‘Ere long a foul, unwholesome lake they nigh, / with swamp-like moat girding a castle round, / at the hour when the sun appears to leap / down to vasty den of night and sleep.’

This is a place of magic; what is more, of evil magic: the lake and the moat around the castle are described in threatening terms (‘foul’, ‘unwholesome,’ swamp-like’ sound noxious for body and soul). But the worst is that, although we were told only a few lines back that Tancred ‘sees with serene forehead rise / Aurora in the white and crimson skies’, this is a world about to be steeped in night. The pace of the narrative does not allow for so much time to have elapsed that it is already the end of day. Some devilry is at work here.

Still, Tancred follows the false courier, taken in by his plausible lie that this castle used to belong to Saracens (which would explain the foulness), but now it is conquered by Count Cosenza – a fictitious name of a non-existent character. Tancred begins to have misgivings about the whole thing. What worries him most is the castle itself. ‘Somewhat he suspects that such a strong / castle might hide entrapment or betrayal.’ He too recognizes the castle, as any reader of the romance would (and this includes us modern readers), as a potential place of danger. Yet he is so fearless, Tasso tells us, that he walks in; and then of course the game is up, and Tancred realizes that this is indeed a trap. An ‘armoured knight’ ‘with fierce and scornful air’ appears and tells him what he has got himself into:

O you, who (led by Fortune or your will) / have set foot in Armida’s fatal lands, / think not of flight, but straight your weapons spill / and into shackled thrust your caitiff hands. / Seek not to cross her guarded threshold till / you bow to the law that binds her warrior-bands, / nor ever hope to see the sky once more, / though years roll past and all your locks turn hoar, / unless you swear to join her men and ride / against whoever fights in Jesus’ name.

So, Armida is behind all this! And this is what happened to those knights who followed her, beguiled by her fraudulent tale! This knight is In fact one of Tancred’s former brothers-in-arms, Rambault, now a renegade and Armida’s pawn. And as Tancred, furious with the deception and the additional insult of submitting to it, is getting ready to fight him, darkness falls and ‘nothing could be seen’. But what follows is a splendid image of potent visual magic, between illusion and reality:

at once a thousand torches, clear and bright,/ suffused the region with a golden sheen./ The castle glows as on a festive night / in a gilded theatre some lofty scene, / and, perched on high, Armida sits at ease, / hid where, though unseen, she both hears and sees.

Tasso, living in an enlightened age, prefers to invoke the enchantment performed by theatrical illusion rather than the supernatural workings of actual magic. A spectacle is about to unfold and it is all the work of a hidden illusionist, Armida, who is also the only spectator.

A fierce combat between the two knights follows, in which Tancred seems to be winning: he chases his foe to the bridge of the castle and is ready to strike the final blow:

when lo! (help from on high to the wretch) all light / of torches ceased, and of all stars beside, / and to blind night, beneath a sky bereft / no ray, not even the pale moon’s, was left.

Tancred is left in the dark, because of Armida’s dirty trick, and now the battle is lost. He is trapped in an ‘uncanny prison’, and it was all his fault, for he ‘went / willingly in and found himself confined / in a den no man leaves by his own intent.’ He gropes about in the dark and pounds at the gate but to no avail. And to spell out his doom, a voice is heard in the dark:

Hear you – fear not to die yet! – shall drag out,

entombed in living death, your days and years.

This magical scene, possibly inspired by a scene in The Iliad where the goddess Aphrodite protects Paris from Menelaus by casting a dark cloud over him, inspired other poets in its turn; for example Edmund Spenser in The Faerie Queene (see Harold H. Blanchard, ‘Imitations from Tasso in the “Faerie Queene”‘, Studies in Philology, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Apr., 1925), pp. 198-221). It is a powerful scene, making use of the primeval fears of the dark and of entrapment, as well as the wonder and delight stirred in our souls when we see a multitude of lights blazing all at once. It is also about the potency of illusion and the bitterness of disillusionment.

It is also another of Tasso’s artful cliffhangers, urging us to read on. What will happen next? Is Tancred doomed? Surely not – but how is he going to break free from Armida’s dark castle?

(1) Jacques Le Goff, Medieval Civilization 400-1500, tr. Julia Barrow (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988), p.131.